By Rabbi Raymond Apple, Senior Rabbi of the Great Synagogue, Sydney

By Rabbi Raymond Apple, Senior Rabbi of the Great Synagogue, Sydney

Mohammed’s description of Jews and Christians as “People of the Book” is particularly apt. The Hebrew Bible (referred to by Christians as the ‘Old Testament’) is indeed the central basis of Judaism. It is not so much a single religious work as a library of books of Jewish history, law, poetry, ethics and philosophy, written and collated over a period of centuries.

The Hebrew word for the Bible is the TaNaKH, an acronym standing for Torah (the Five Books of Moses), Nevi’im (historical and prophetic books) and Ketuvim (other sacred writings such as Psalms and Proverbs).

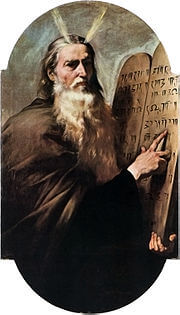

The first five books of the Bible, described as the Torah, comprise both an early history of mankind and of the Jewish people, and a code of Divine commandments, which are holy, binding and authoritative for the traditional believing Jew. Its author is regarded as God, though the actual writing down of the material was by Moses.

With the written Torah came the ‘Oral Law’, a large body of explanatory material which orthodox Jews regard as having been transmitted by God to Moses and originally passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. Thus each generation found insights in the Torah, but believed them to have been latent in the traditional material. Though this tradition continued to be called the oral Torah, in fact it began to take written form in the early centuries of the Common Era, probably first in written notes and then in extensive written works.

The oral Torah grew over the ages and became so extensive that in the 2nd century CE it was edited into a single text. In the original form, with the name ‘Midrash’ (‘seeking out), it had followed the sequence of the Biblical text, but later it was re-organised under subject headings and known as the ‘Mishnah’ (‘repetition’, probably because it was learned by rote memorisation).

The Midrash covered both legal and ritual teachings (halakhah) and historical and philosophical material (aggadah). The halakhic aspect was easier to handle in Mishnah form, and the Mishnah covers practical subjects as diverse as prayer and worship, agricultural work, Sabbath and festivals, marriage and divorce, civil and criminal law, Temple rituals, food laws and rules of ritual purity. The Mishnah was edited in the 2nd century CE by Rabbi Judah HaNasi (‘the Prince’).

During the next few centuries rabbinical analysis of the Mishnah, known as ‘Gemara’, continued with the participation of many of the people as a whole, especially during two months of the year when agricultural work was not demanding and most people had time to devote to study. The extensive combined version of Mishnah and Gemara became known as the ‘Talmud’ (‘learning’). There are two versions of the Talmud, the Babylonian Talmud, which is larger and more authoritative, and the Jerusalem Talmud. References to “the Talmud” are to the Babylonian Talmud.

Aggadah continued to develop separately in the Midrash form, providing an extensive commentary on the Biblical text. Much Midrash material began as sermons in which the weekly scriptural lessons were expounded before an ancient congregation.

The language of the Midrash is Hebrew; Talmudic material is in a combination of Hebrew and Aramaic, an associated Semitic language. (Aramaic was the language of the Assyrian conquerors, adopted by the Babylonians, which became the dominant language of the Middle East, and it is used in a number of Jewish prayers and documents.)

Jewish religious writings may be categorised as summarised below, though there is really no demarcation between “religious” and “secular” works in traditional Judaism, which deems everything to be part of one whole. Ideological secularism is a modern development; and some Jewish thinkers like Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook have argued that the so-called secularist or atheist is deep-down a believer seeking spirituality.

Post-Talmudic categories of Jewish writings include:

Most of the material is written in Hebrew but there were many works in other languages (or Jewish versions of other languages, such as Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, and Yiddish, Judeo-German). Rashi is famous for including medieval French words in his Hebrew commentaries to the Bible and Talmud. There are translations of most classical Jewish writings in English and other languages, and modern authors on Jewish subjects write in a variety of vernaculars.

A basic introduction to the Jewish literature begins in part-time religious schools and Jewish day schools. There is also a Jewish tradition of continuing adult study, including discussion groups studying the Talmud and other Jewish literature organised by most synagogues. Many universities offer courses in Jewish subjects, and there are “yeshivot” (Talmudical colleges) in major cities. A great help has been the development of modern means of technological communication, especially the Internet, which enables anyone with access to a computer to open up what might once have been a closed world.

© Rabbi Raymond Apple 2004

The word ‘Midrash’ comes from the Hebrew root darash meaning ‘to investigate’ or to ‘seek out’. Indeed Midrash is exactly that—it is an investigation of the Biblical text in order to try and probe its deeper meaning/s.

Midrash therefore refers to both a method of interpretation (exegesis) and a body of literature that is a result of this literary methodology.

Midrash is an ancient form of exegesis but it continues to be practiced in Jewish communities in the present as Jews continue to search for meaning and relevance in their sacred texts. According to James Kugel (in The Bible As It Was) Midrashic method rests upon four basic assumptions concerning the Biblical text:

Midrash can begin as word play, a concern with textual irregularity, word play, parable and all of the above. Ultimately it seeks to provide a ‘lesson’ of sorts—whether that be to expound a verse more clearly and with greater relevance to contemporary communal needs, to make a political or theological point or seek out an answer to a question posed by the text itself. It is a varied and immense literature spanning the entirety of Scripture, beginning, some argue, within the Biblical text itself, reaching its greatest heights in classical Rabbinic literature and continuing into the present day.

Midrash is a corpus of literature that has enabled Jewish communities to remain in dialogue with a living Biblical text—bridging the gap between past and future—and enabling the text to intersect and inform the day-to-day life of generations of Jewish communities.

© Avril Alba, Director of Education, Sydney Jewish Museum, 2005

A Midrash tells us that during the seven days when Moses was at the burning bush each day he pleaded with God to send someone else). In the end of the Midrash, God informs Moses that because of his unwillingness to take on the task during those seven days he will not be permitted to ascend to the priesthood. Rather, it is Aaron and his descendants who will become the priests. However, for seven days, when the Tabernacle is dedicated, Moses will be allowed to perform the priestly functions, but not after that.

Moses’ reaction to what might be perceived as a punishment is to rejoice over the good fortune of his elder brother Aaron. After all, Midrash tells us, one reason why Moses is reluctant to take on the leadership role is because he is afraid that Aaron will be jealous that his younger brother is the leader of the people. However, God informs him that Aaron will rejoice at seeing Moses and hearing that he is to lead the mission to Pharaoh, and indeed he does. For this Aaron is rewarded; let “that same heart that rejoiced in the greatness of his brother [have] precious stones (the priestly breastplate) set upon it.”

And so Aaron rejoices at God’s choice of Moses as leader and Moses then rejoices at the choice of Aaron as high priest, even though the Midrash portrays this as Moses’ punishment for not being eager to go on God’s mission. Nevertheless, when Moses is given the instructions on how to build the Tabernacle he tells God in a Midrash that he is ready and able to serve as priest. How can this be so if had been informed at the burning bush that Aaron was to serve priest and if Moses himself had actually rejoiced over this? We all know of times in our lives when we “conveniently” forget something and then are stunned when we later “discover” it. When Moses “learns” that Aaron is to become priest and that he is to be “demoted” to the status of a mere Levite (as will his sons) he does not react negatively. Rather, he rejoices, just as Aaron rejoiced in Moses’ choice earlier on.

The choice of Aaron, the elder brother, as priest now means that the rejection of the elder in favor of the younger that runs through the entire book of Bereshit/Genesis has now been “set right.” Moses, the younger, may indeed be the leader, but his sons not only do not inherit his position, but they are all but forgotten in our narrative. It is Aaron, the elder, who is given the religious leadership position that will then be inherited by his sons.

The rejection of Moses and his sons and the reversal of the ancient patterns could easily be viewed by Moses with anger or disdain. And yet it is not. The relationship between Moses and Aaron is one that involves both loss and gain for each brother while at the same time involving altruistic love of each brother for the other that is symbolized by their reactions when the other is chosen.

In the Torah we are told that Moses’ primary attributes were that of greatness and humility. In reality it is his humility that is at the heart of his greatness. Though Aaron is appointed “kohen gadol” (literally, great priest) Moses’ humility allows him to rejoice, much as his humility caused him to reject God’s initial call for fear that Aaron would be hurt.

This is the meaning underlying the seemingly innocuous “and as for you” that begins the command for Moses to prepare the oil, decorate the courtyard of the Tabernacle and instruct others to prepare Aaron’s garments. In this way the “and as for you” is not viewed as further punishment for Moses’ initial reticence (i.e., God saying “And as for you if you’re going to hesitate to follow my orders not only am I going to take away the priesthood, but I am going to make you prepare everything for your brother the priest and then let you serve as priest for seven days only so you can then hand the duties over to him!”)

Instead, it becomes an acknowledgement of Moses’ humility and his ability to rejoice for his brother (Read as, “And as for you, you have shown your greatness through your humility and your concern for your brother, and so you shall have the pleasure of preparing all that he needs to begin his priestly service, including dedicating the sanctuary that is then to be his domain from then on.”)

(Adapted by Avril Alba from www2.jrf.org/recon-dt/dt.php?id=73)

For extracts from the literature which demonstrate the principal beliefs of Judaism, see Core Ethical Teachings of Judaism