Moses is the key figure in Jewish history, described as the greatest of all the prophets. He was the person privileged to receive the Torah (Jewish Law) on Mt Sinai. According to Jewish tradition, he is the only human to have ‘seen’ G-d, in a dramatic encounter described in Exodus 33-34.

Moses the Man

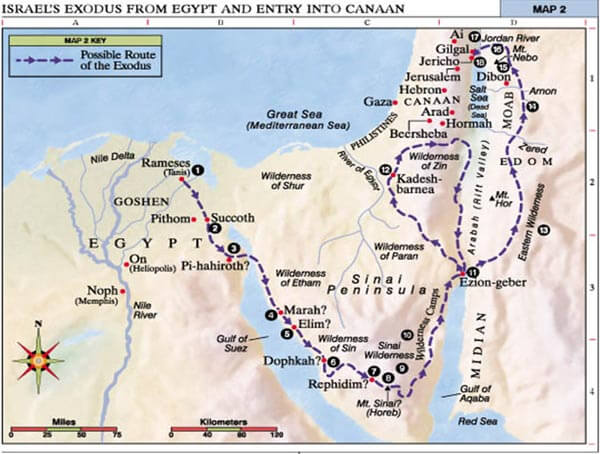

Moses is born in difficult circumstances. His very survival is miraculous. The Children of Israel are enslaved in Egypt and a decree is issued that all baby boys are to be drowned in the River Nile. Moses’ mother and sister contrive to save him by first hiding his birth and then putting him into a basket that will float on the River. Moses’ sister, Miriam, watches as Pharoah’s daughter finds the basket and rescues the baby, eventually bringing him up as her own child.

The Biblical text does not explain whether Moses’ Jewish identity is hidden from Pharoah or how Moses himself comes to learn that he is a Jew, but when “he grew older” he “went down to his brothers and saw their burdens” (Exodus 2:11). From that moment onwards, Moses demonstrated the qualities of leadership that were to characterize him until he was 120 years old. The Biblical narrative from the Book of Exodus until the end of Deuteronomy (4 of the 5 Books of the Torah) chronicles his life. It is the story of a remarkable human being, one not free of human flaws, but one nevertheless endowed with qualities that enable him to lead his people from slavery to the verge of independence in their Promised Land.